It is when we know what, and how much is thrown away can we begin to tackle the food loss problem.

Loss and waste are rife across the food supply chain. And over the past few weeks, as part of our #FLWDay initiative, we’ve spoken abundantly about why it matters, and how to curb it. We now wanted to know if businesses were measuring food loss. And if they were, was it reported?

With that bee in our bonnet, we kept the spotlight on businesses that address post-harvest handling and storage, processing, manufacturing, etc.

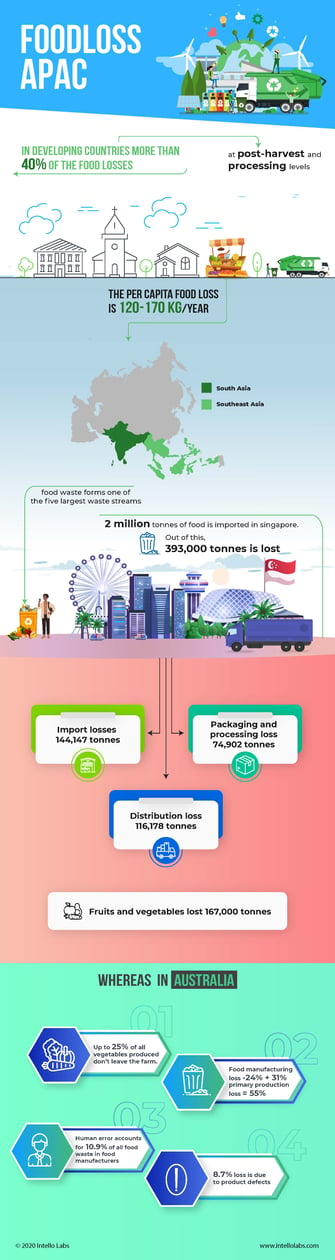

Why? Because the food supply chain is only as strong as its weakest link. And the darkest pits of food loss are present upstream and midstream, particularly in South and Southeast Asia.

Spoiler: there is a huge data shortage on food loss.

The data deficit on Singapore’s food loss

From farm to market, 342,000 tonnes of food is lost in Singapore. The dollar value of this is 2.54 billion per year. There is a whole host of reasons food is tossed:

- Over-importation.

- Handling and damage during transport.

- Delay in shipments that lead to not fresh enough produce.

- Sorting out of any food that fails to meet high cosmetic standards.

- Packaging and trimming before shipment.

144,000 tonnes are lost when imported food reaches the city-state, and nearly 75,000 tonnes during processing. Yet import, packaging and processing businesses do not measure the weight of discarded food.

They do assess the economic value of the food loss (approximately 2% to 3%) but don’t go beyond it. Why? Because by selling the leftover food, which is about half of what was imported, they still make a net profit.

Singapore is not alone when it comes to abysmal food loss data. Australian businesses float in the same boat.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”5/12″][vc_single_image image=”9261″ img_size=”full” alignment=”center”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

The weak supply of Australia’s food loss data

In a year, the total food loss and waste cost Australia over $20 Billion. 55% of it happens during primary production and manufacturing. But when you look for detailed recording of this loss, there is hardly any available.

According to the National Food Waste Baseline Report, there are about 85,000 primary production businesses in the country. And while there is an estimate of how much food loss occurs here, the majority of which is from fruits and vegetables, actual data is limited.

It’s the same story for manufacturing/processing, which has 13,300 businesses. Measurement of food loss here is variable. Some companies take the pains to quantify it, but most don’t.

Why are Australian businesses not measuring food loss? At the primary production link of the supply chain, some challenges make quantifying the loss difficult. For instance, farmers have a sense of the proportion of food lost, but not exhaustive and measured quantities.

At the manufacturing level, some do track food loss, but as a degree of cost, not quantity. For most, the financial damage is not enough motivation to measure the waste. The absence of mandatory reporting is one more reason for it.

If you can’t measure, you can’t manage

There is no silver bullet to cut food loss. That said, anyone can develop a food loss minimisation plan. But for the plan to be impactful, you need to know where food is lost.

It’s as simple as ‘what gets measured, gets managed.’

When you fail to measure food loss, you can’t manage it because a) you can’t pinpoint the hotspots b) you cannot create relevant business practices and c) you can’t monitor progress.

Take, for example, the UK’s Waste and Resources Action Programme. WRAP realised that their food loss and waste data had significant gaps. So, under the Courtauld Commitment 3, it introduced the Food Waste Reduction Roadmap to help businesses ‘work out what types of waste to measure and how to measure it.’

The approach set within the roadmap is Target, Measure, Act, using which plenty of businesses have lessened food loss. Two examples are Tesco suppliers G’s Fresh and A Gomez. Both of whom reduced food loss by 22% and 48%, respectively, in one year.

A big fish example of why you need to measure food loss is Unilever. The FMCG giant uses the FLW Standard to quantify how much food is lost in its manufacturing operations. It began measuring in 2016 and realised that for every tonne they produced, they threw away 363 g. By 2019, they reduced that number to 193 g.

By quantifying, Unilever could also see that they were better off focusing on saving food loss across their value chain, not just direct operations.

The path to measuring food loss

A study affirms that human error is responsible for 10.9% of all food waste in manufacturing processes. 8.7% is attributed to product defects. In monetary terms, i.e. the true cost of food loss to a business, it is enough to make you sit up and notice.

A Champions 12.3 report states for every dollar you invest in curbing loss, you save fourteen. Yet most companies don’t even think about determining how much they throw away. That’s why measuring food loss is critical.

So, how does an up and midstream food business track and limit food loss? We think the simplest answer is utilising sorting and grading technology because it can recover rejected produce and find more suitable purposes for it.

But then, we are somewhat biased!

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

.png)